The History of the Aboriginal Art Movement

While Aboriginal art has been around for tens of thousands of years, the Aboriginal Art Movement, and in particular painting, has more recent origins.

Today’s Art – The Beginnings

In the 1934, two Melbourne artists visited the Hermannsburg mission, roughly 130kms west of Alice Springs. After viewing the artist’s watercolours, a local Aranda man called Albert Namatjira was inspired to paint and was taught by Rex Batterbee in the style of landscape watercolours on board. Albert Namatjira became a famous artist and is considered one of Australia’s great artists. Albert’s success inspired many other Indigenous people to start painting, though at that time, they followed Albert’s and Batterbee’s style.

Until the early 1970s, watercolour was the primary medium used, although some ochre and bark-style paintings started to become available for non-aboriginal audiences in the 1940s. In 1948 an art and craft centre was also established at Ernabella mission.

Then in 1971, the Aboriginal art world changed dramatically. A young school teacher called Geoffrey Bardon arrived at the Papunya settlement - 250 kilometres west of Alice Springs - and encouraged the local children to draw and paint the stories from their culture. This soon drew the attention of the tribal elders, who were intrigued by the interest the white man showed in their culture.

This led to the creation of a beautiful mural on the school building in Papunya. As interest grew in the community, Geoffrey Bardon began supplying the male tribal elders with acrylics and board to paint on. Although Bardon was only at Papunya for 18 months, he made a significant contribution and assisted the Aboriginal people of Papunya as they developed their own painting styles and representations of their land, culture and ceremonies. By the time Bardon left in August 1972, the elders had created over 1,000 paintings, Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd had been incorporated by the artists and the Aboriginal art movement was well and truly established.

The early years (1972-1981) were a struggle, as there were financial challenges and a constant battle to achieve recognition from an essentially conservative, white audience. This is why there are numerous stories of art, later regarded as masterpieces, being sold for a pittance and major, seminal works of art hanging unrecognised or being stored with other objects of ‘little worth’ in warehouses and garden sheds for many years.

What is lesser known is that artists from the early years also encountered serious resistance and sometimes rejection from other Aboriginal communities who regarded paintings of such sensitive matters as being entirely inappropriate. However, this resistance also contributed to the current practice of representing sensitive matters in a stylised manner, ensuring that uninitiated persons cannot understand the full story behind a picture. Some of the resistance has simply decreased naturally as time has gone by, but the uninitiated will never be told the full story behind many pieces.

Crossing the Barriers

Aboriginal art had taken its first big step in reaching the consciousness of a wider audience, when Clifford Possum and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri’s artworks were included in the 1981 Australian Perspecta exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The development of Artist Cooperatives started to spread through the Aboriginal settlements which had originally been established as part of the government's efforts to assimilate Indigenous people into white society. The funds generated also helped fuel the ‘homelands movement’ – where people returned back to their traditional lands where they established their own communities – such as places like Kintore (Interestingly, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa was heavily involved in the homelands movement!).

By the mid 1980s, painters from Yuendumu had been involved in a successful private exhibition in Sydney and established their own artists’ organisation. The momentum was building, success breeding success. At the same time, ochre based art in the Kimberleys and bark art in Arnhem Land started to receive popular acclaim. The movement was broadening its geographical base.

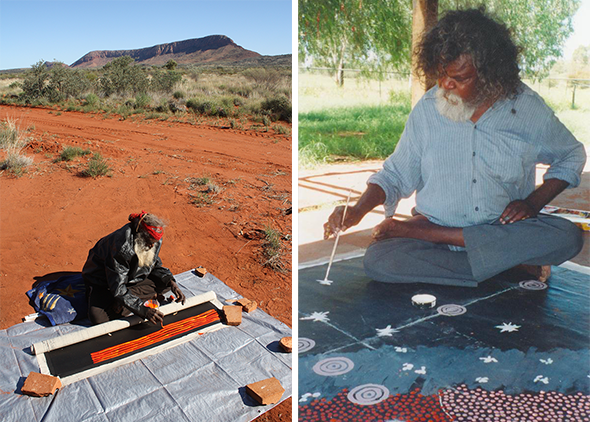

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa & Clifford Possum

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa & Clifford Possum

Recognition by Government, the Establishment and the Market

In 1988, the Australian Federal Government gave the Aboriginal art movement a further boost by accepting Michael Nelson Jagamarra's design for the mosaic in the forecourt of the new parliament house. This momentum continued into and through the 1990s with the art form steadily insinuating its way into non-indigenous Australia's consciousness.

The Sydney Olympics proved another key stepping stone for the movement when Aboriginal art received headline acclaim.

However, as is often typical, a country does not realise what it has until others start to take significant interest. In the case of Aboriginal art, the 2006 opening of the Musee Quai Branly, a dedicated Indigenous art museum in Paris, brought international attention to Australian Aboriginal art.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

May 2007 saw the first piece of indigenous art sold for more than $1 million, the Emily Kame Kngwarreye piece, Earth's Creation. It was a record price not only for Australian aboriginal art, but also for any Australian woman artist. This record was swiftly followed by the sale in July 2007 of one of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's acclaimed "map series" which reached $2.4 million. In two short months, Australian Aboriginal art had emphatically announced itself as a serious art form for the collector and the investor alike.

Hot on the heels of this incredible financial vote of confidence came the Culture Warriors exhibition at the Australian National Gallery. The exhibition was to be the first of a series of triennials exclusively featuring Australian Indigenous art. It seemed that a bright future was assured after 30 years of struggle.

However, 2008 saw Australia hit by the global financial crisis. The impact on Australian Aboriginal art was dramatic as financial pressures resulted in numerous gallery closures, the consequent loss of outlets for artists and the art regressing in consumers’ minds as more pressing financial matters took precedence. So, just as the art truly hit the headlines, it suffered its worst set back.

The intervening years have seen a rationalisation of the industry, some would say a necessary rationalisation. What is indisputable is that the slowdown has definitely led to an overall improvement in the artworks being brought to market. At the same time however, the original pioneer artists continue to pass away, so many of the links back to the origins of the movement have been lost.

The period from 2014 forward has seen renewed confidence in the sector. The galleries trading tend to be well established and well funded, with the capacity to foster and support emerging artists. The artists represented represent the best of the old masters and the new generations coming through, developing their own styles and their own unique takes on the ancient stories.

Timmy Payungka & Sarrita King

Related Topics:

Body Paint and Ceremonial Artifacts

Rock Art from the Kimberleys

Types of Aboriginal Art

Modern and Contemporary Aboriginal Art