Defining Tradition | the first wave and & its disciples

19 january - 17 february 2019

article | related videos | exhibition catalogue | online exhibition

This year, we thought we’d try something different with our exhibition schedule. Don’t worry, the stellar solo shows and hugely popular artist in residence programs will still appear in the 2019 calendar, but we also wanted to provide our art-loving clients with some more weighty exhibitions to help contextualise the 2,0+ artworks stored in our gallery. So, starting in January 2019 we’ll kick off a series of exhibitions exploring the notion of ‘tradition’ in Aboriginal Art [1].

Aboriginal art is clearly in a category of its own and whilst it may be tempting to use modern art criteria to assess the works, Aboriginal art does not fit neatly into the mould of art in the Western sense. The world’s oldest living culture is organic and constantly evolving. So too is its art. And after over 40 years of employing non-indigenous media, the history of contemporary Indigenous art in Australia is marked by stories of great artists who have inspired other close or extended kin to follow their direction, resulting in a number of distinct schools, lineages or ‘traditions’.

The first wave & its disciples will present artists that have remained faithful disciples of the muted colour palettes and powerful expression of Tjukurrpa (Dreaming) as first set down by the pioneers of western desert art, those present in the remote community of Papunya in 1971.

So – where to begin our ‘defining tradition’ exhibition series? For us the answer was quite clear, as we are fortunate enough to have this exceptional piece by one of the founding Papunya Tula artists hanging in our gallery:

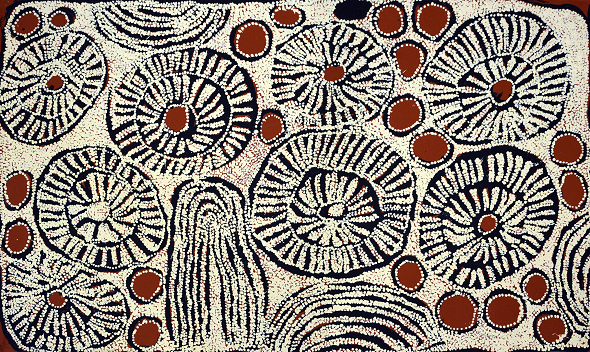

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula 'Water Dreaming Kalipinypa' JWJG0001 122 x 211cm

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula 'Water Dreaming Kalipinypa' JWJG0001 122 x 211cm

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula was part of the Old Pintupi [2] when Geoff Bardon arrived in Papunya and was one of eight men in the first Papunya consignments to the Stuart Art Centre in 1971.

Johnny rapidly developed a distinctive style of his own which came to be known as 'over-dotting'. He uses several layers of dots to depict his Dreamings, which consist of Water, Fire, Yam and Egret stories. Geoffrey Bardon labelled this stylistic layering effect as 'tremulous illusion' and in his book Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert, Bardon fondly recollects images of Johnny painting with an "intense level of intuitive concentration".

This piece was painted in 1999 and features the established imagery of Johnny's Dreamings overpainted to hide the secret and sacred elements. Where he was once known for his delicate and soft white dotting, he attacked the canvas to tell the story with great gusto. He jabbed large dots on to the surface and produced roundels and symbols for weapons with great sweeps of his arm and the brush. After nearly 30 years of painting, and perhaps due to his failing health and eye-sight, Johnny painted with a new-found freedom, both in expression and in painting technique.

The combination of Tingari or Dreaming motifs used to describe the culture and country of these senior men formed the basis of the abstracted dot designs that both described and disguised some of the great creation narratives from their heritage.

Our exhibition title ‘the first wave & its disciples' references this first wave of artists who painted in such a manner, and the faithful disciples who have maintained their artistic traditions. Many of these disciples began their artistic practice by assisting family members to infill areas of the background of the paintings; a collaborative process which was instrumental in the development of future generations of painters. As male collaborators themselves became artists in their own right, the role of women as assistants began.

Johnny Yungut Tjupurrula's tutelage had obvious incarnations in his wife, Walangkura Napanagka's works. Johnny Yungut was an "integral part of the Papunya Tula Artists for his entire artistic career, as well as being a highly respected cultural figure within the Pintupi Community" [3]. Tracks and features of the land are outlined in solid black brushstrokes, followed by meticulous dot work in vivid orange red and yellow.

Returning to their traditional country during the homelands movement of the 1980s, Walangkura participated in the historic women's collaborative painting project in Kintore in 1994 that was initiated by the older women as a means of re-affirming their own spiritual and ancestral roots. The huge and colourful canvases that emerged from the women's camp were 'alive with the ritual excitement and narrative intensity of the occasion' (Johnson 2000: 197). Within a year, Papunya Tula Artists, now established at Kintore, had taken on many of these women as full-time artists, revitalising the company after the deaths of many of the original 'painting men'.

Walangkura Napanangka, 'Tjintjintjin' WNAS0004,138 x 138cm, Acrylic on Linen

Walangkura Napanangka, 'Tjintjintjin' WNAS0004,138 x 138cm, Acrylic on Linen

Walangkura's early works created from 1996 onward are characterised by masses of small markings and motifs covering large areas of canvas. Her favourite colour, a deep sandy orange predominates, accentuated against more sombre blacks and reds and dusky greens or yellows. More recent works show a gestural quality though still tightly packed with an intensity of geometric line work representing sand-hills. Like Johnny Yungut's, these dynamic compositions are singular in their vision and voice and now Walangkura’s eldest daughter, Debra Young Nakamarra, also creates works of unique energy and vigour.

The widow of Yala Yala Gibbs Tjungurrayi (a highly respected Pintupi elder who held significant knowledge of his countries Dreaming stories), Ningura Napurrula, first began to paint in her own right in 1995 in the second year of the Haasts Bluff/Kintore women’s painting project. Whilst Ningura’s art may appear looser and more tranquil, there is a strong narrative element to her paintings.

Ningura Napurrula 'Wirrulnga' NING0017 92 x 151cm, Acrylic on Linen

Ningura Napurrula 'Wirrulnga' NING0017 92 x 151cm, Acrylic on Linen

Her use of a limited palette emphasises the structural elements of her work and slight tonal variations of cream and white move the viewer’s eye around the surface of the paintings. Yala Yala Gibbs used a similar limited colour palette, in works such as Yawulyurru (1972, NGV Collection). Ningura's paintings often relate to the rock-hole sites of Wirrulnga and Ngaminya, which are to the east of Kiwirrkurra. The site of Wirrulnga is associated with birth; at these sites women hair is spun to form nyimparra (hair-string skirts) which are worn during ceremony.

Yinarupa Nangala was a co-wife with, amongst others, Ningura Napurrula, of Yala Yala Gibbs. Yinarupa also started to paint in 1996. However, for some time she gained only moderate recognition for her works. This gradually changed in the late 2000s and by 2009 her austere style was finally recognised for what it is, classic Pintupi art at its best.

Yinarupa Nangala 'Untitled – YNAG0059', 150 x 209cm, Acrylic on Linen

Yinarupa Nangala 'Untitled – YNAG0059', 150 x 209cm, Acrylic on Linen

She paints the country around Mukula and the women's ceremony associated with it. The story is passed down from her father's mother. The shapes in the painting represent the features of the country, as well as bush foods. Women are represented by the 'U' shapes and kampararpa berries are represented by the circles. The tree like shapes that run across her paintings are the trees used to make spears. This is Yinarupa's unique representation of the story that Turkey Tolsen and his sister, Mitjili Napurrula, paint (both of whom are also family).

Pulling the show together is Naata Nungurrayi’s exceptional work Marrapinti. Naata’s paintings combine the carefully composed geometric style that developed at Papunya amongst the Pintupi painting men, with the looser technique and more painterly organic style introduced by the women after the paintings camps of the early and mid 1990s.

Naata Nungurrayi 'Marrapinti – NA201228', 183 x 245cm, Acrylic on Linen

Naata Nungurrayi 'Marrapinti – NA201228', 183 x 245cm, Acrylic on Linen

The western desert painting movement initiated by senior Pintupi men in the early 1970s has developed at a rapid pace and pushed down new pathways, some of which we will explore in upcoming exhibitions. The first wave & its disciples is a thoughtful collection of works from the Kate Owen Gallery stockroom which provides a way of looking back while looking forward.

Related Videos

[1]All too often in the gallery, the word ‘traditional’ is thrown around – what does that mean and look like with regards to Aboriginal Art?

Our common understanding of the word ‘traditional’ is as something existing in or as part of a tradition; something long-established.

It is useful to look at the concept of “traditional” in the context of the western desert art movement. In 1971 in the community of Papunya, a group of Pintupi, Luritja, Arrernte, Anmatyerre and Warlpiri men began to turn traditional designs involved in ceremony, body decoration and cave painting into a new and commoditised form – acrylic paintings on a flat surface.

In 1982 archaeologist Vincent Megaw pointed out that this art cannot really be described as ‘traditional’ since it began with interactions with a cultural outsider, Geoff Bardon, the works are produced for an external market and are not produced for local use. Yet, as Fred Meyers explains, the formal elements and inspiration for most of the paintings, early and late, grew out of an Indigenous system of representing in visual media.

Perhaps that is why the term ‘contemporary Aboriginal art’ came in to the play – ‘contemporary’ simply means ‘to be of one’s time’, which is precisely what the art produced since 1971 in Papunya has been; artists laying down their ancient Tjukurrpa and tradition of ritual on and with new artistic media. Yes, the art is produced for an external market and has become an object of trade, but the intellectual content is inherent and, as Jennifer Isaacs described, is a way of spreading information and knowledge, and strengthening Aboriginal power.

[2] ‘Old Pintupi’ refers to the Pintupi people in Papunya who had experienced longer and more direct contact with the Lutheran missionaries and government officials as opposed to the ‘New Pintupi’ who arrived in Papunya in the early 1960s.

[3] Papunya Tula Artists, JOHNNY YUNGUT TJUPURRULA @ ReDot Gallery Singapore, Nov 2 – Dec 8, 2017